Not long ago, in front of a Senate panel, Dr. Oz (the most trusted doctor in America) was told by Senator Claire McCaskill “I don’t get why you need to say this stuff because you know its not true.” Senator McCaskill was referring to the many “miracle” weight loss supplements that Dr. Oz promotes on his show, but she could easily have been referring to any number of other topics that the TV doctor has addressed. In particular, Dr. Oz has been a regular critic of crop biotechnology, or GMOs, and has featured a who’s who cast of anti-GMO activists.

Dr. Oz recently aired another segment related to GMOs, part of which focused on the new Enlist Duo corn & soybean herbicide. Steve Savage has already deconstructed quite a few of the misleading statements Dr. Oz presents in the segment. But I wanted to quickly address a second segment on the show, where Dr. Oz blows feathers all over the stage (clearly using a large fan off-camera to his right) to try and scare the bejeezus out of you to illustrate pesticide drift.

Although this is a powerful visual demonstration, it grossly misrepresents the actual amount of off-target pesticide movement that we would expect when crop fields are sprayed. And we know this because there is a large (and continually growing) body of research on this very topic. Active public and private research programs around the world have been investigating ways to reduce pesticide drift for well over 40 years. I can assure Dr. Oz that pesticide applications are quite a bit more precise than dumping feathers on a stage behind a fan.

I recently addressed one aspect of off-target pesticide movement in response to an EWG report. In a nutshell I concluded that:

“…even if [a] 20 kg child ran around in the sprayed field continuously for 24 straight hours, they would only be exposed to a maximum of 0.0097 mg/day, 14 times less than what would be considered safe using EWG’s proposed standard. So even if we assume very high estimates of air concentration, assume very high breathing rates of children, assume a very small child, assume unrealistically high exposure time, and assume an unrealistically close proximity between the child and the treated area, there is nothing to indicate the children would be exposed to unsafe concentrations of the herbicide. If we use more realistic values for each step (proximity, concentrations, breathing rates), the chronic exposure would be almost negligible.”

There are two primary ways that pesticides can drift off-target; the pesticide spray droplets can be blown off-site during the spray application (particle drift), or the pesticide can volatilize after application (vapor drift). In my previous post, I only focused on vapor drift:

“I’ve only addressed concentrations due to volatility; I did not include the potential impact of particle drift. Certainly, there is potential for increased drift of the herbicide on the day of herbicide application, if wind is blowing from the field toward the school, and the applicator is not taking appropriate steps to minimize drift potential. But, realistically, this would occur a maximum of 3 times per year (on the day when applications are actually being made).”

So what is the potential for spray droplets to move off-site during the spray operation? Will it look similar to dumping a bucket of feathers behind a fan?

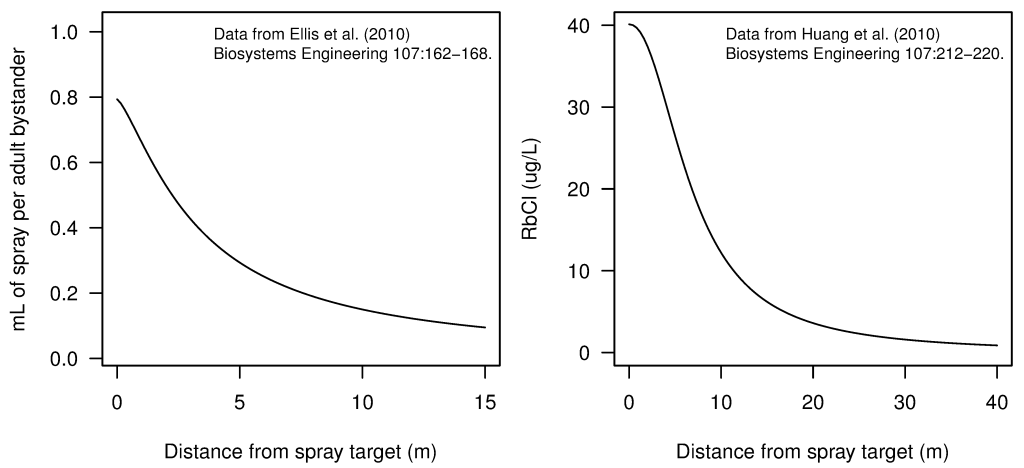

I found two fairly recent articles that have measured spray drift from pesticide applications. Again, pesticide drift is a pretty large body of research, and I didn’t take the time to sort through hundreds of papers. But I think these two papers combined give us enough information to get a reasonable estimate of how much pesticide we might expect to be exposed to if we were in the vicinity when the application was being made. The first paper (Ellis et al. 2010) measured the amount of spray volume bystanders (either volunteers or mannequins) came into contact with when standing from 2 to 12 meters (6.5 to 40 feet) away from the spray boom. That data is really cool, and relevant, but is pretty limited with respect to distance. There simply aren’t very many people that will be standing within 40 feet of a field while it is being sprayed, and certainly not many of the general public that make up Dr. Oz’s audience.

A second study by Huang et al. (2010) use a little different methodology, but measure the amount of spray application that moved up to 45 meters away from the spray target. Huang et al. present the information in a way that is difficult to convert to direct human exposure. But it provides estimates for drift between 5 and 45 meters from the spray target.

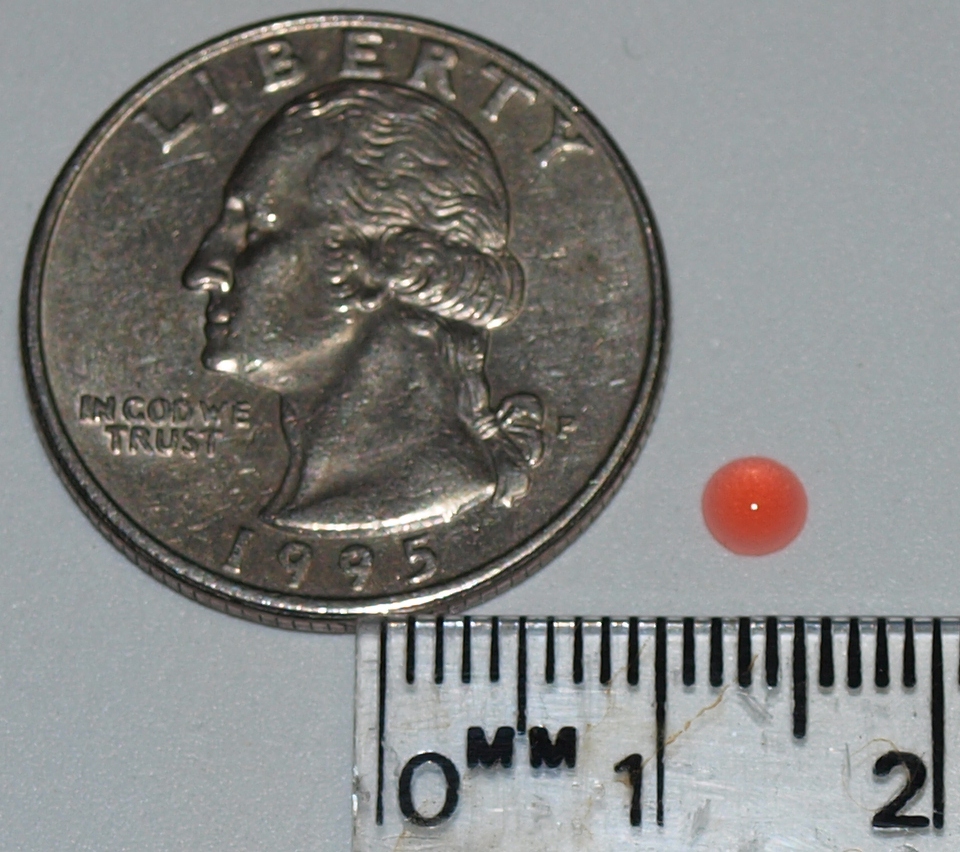

Based on the Ellis data, we can estimate that an adult standing 10 meters downwind from the sprayer would be exposed to 0.15 millilitres (mL) of spray solution. During the Ellis trials, wind speeds were between 5 and 10 miles per hour. For longer distances from the sprayed field, we can get an estimate from the Huang data. The estimated concentration at 40 meters in that study was 93% less compared to the concentration at 10 meters from the sprayer. If we apply that same reduction to the Ellis data (which uses humans as the target), we can estimate that a person standing 40 meters (about 130 feet) from the sprayer might be exposed to 10.7 microliters (uL) of spray. If you don’t work in a laboratory, it can be pretty difficult to visualize what 10.7 microliters actually looks like. I took a photograph of a 10.7 microliter droplet (of red food coloring) to put it in perspective.

The dose makes the poison, and that’s a pretty small dose. Now there may be some chemicals for which 10.7 microliters is a dangerous exposure, but for glyphosate and 2,4-D (the active ingredients in Enlist Duo) this amount is certainly within safe limits. It is also important to remember that this droplet represents the amount of total spray solution at 130 feet, not the amount of pesticide. Even with the most concentrated applications, only about 10% of each droplet would actually be pesticide; 90% or more will be just water.

In his recent comments to the Senate panel, Dr. Oz said: “When we write a script, we need to generate enthusiasm and engage the viewer.” It seems to me, that those goals shouldn’t preclude also being accurate.

Comments are closed.