In a recent issue of Nature, Natasha Gilbert took “A hard look at GM crops.” Ms. Gilbert states:

“it can be hard to see where scientific evidence ends and dogma and speculation begin.”

“Researchers, farmers, activists and GM seed companies all stridently promote their views, but the scientific data are often inconclusive or contradictory. Complicated truths have long been obscured by the fierce rhetoric.”

I agree wholeheartedly. Especially when browsing the internet, there is a lot of misinformation, half-truths, and outright lies about GM crops. I’m always glad to see this topic approached with scientific rigor, and I expected an outlet like Nature to do just that. The point of Ms. Gilbert’s article was to separate fact from fiction with respect to some often heard claims about genetically modified (GM) crops. One of the three issues Ms. Gilbert chose to tackle in her article is the claim that “GM crops have bred superweeds,” and she considers this statement “True.”

I was a little disappointed to see the term “superweeds” in any type of scientific publication. I have repeatedly expressed my displeasure with this term, and my graduate students know better than to ever use the word around me. To see it in a publication as reputable as Nature is exceptionally frustrating. But at least this article would be approached with some “scientific evidence” rather than “dogma and speculation”, right? But as I read through the section on superweeds, I saw very little that resembled scientific evidence; rather, lots of opinions, anecdotes, interesting tidbits, some facts and figures, and a fairly compelling narrative. But no “scientific evidence.”

The lack of any scientific evidence in the article probably relates to my biggest problem with the term superweed: nobody seems to know what a superweed is. To determine whether “GM crops have bred superweeds” at least two things are needed:

- a definition of the term superweed, and

- data that relate use of GM crops to development of superweeds.

Let’s begin by trying to define superweed. Certainly, the term indicates that the weed is super in some way; it must possess some trait that is above and beyond an ordinary weed. Like a superhero that has some ability that the general public does not. So what is this “super” trait that superweeds possess? Can a superweed grow faster than the Incredible Hulk? Or can a superweed spin a web like the Amazing Spiderman? Or maybe a superweed can fly like Superman!

Most of the time, the term superweed is associated in some way with herbicide resistance. So if we define superweed as a weed that has evolved resistance to herbicides, we can then test the hypothesis that “GM crops have bred superweeds.” (ASIDE: The way this statement is phrased, there’s no way it can possibly be true, because crops don’t “breed” weeds. There are some rare cases where crops and weeds cross pollinate, but those have not resulted in any herbicide resistant weeds to date. For the sake of argument, we’ll assume Ms. Gilbert really meant “GM crops have significantly increased the development of superweeds.”) Dr. Ian Heap has developed and maintained a website to document new cases of herbicide resistant weeds, and we can use the data at that site to get an idea of whether this statement is true or false using our definition of superweed.

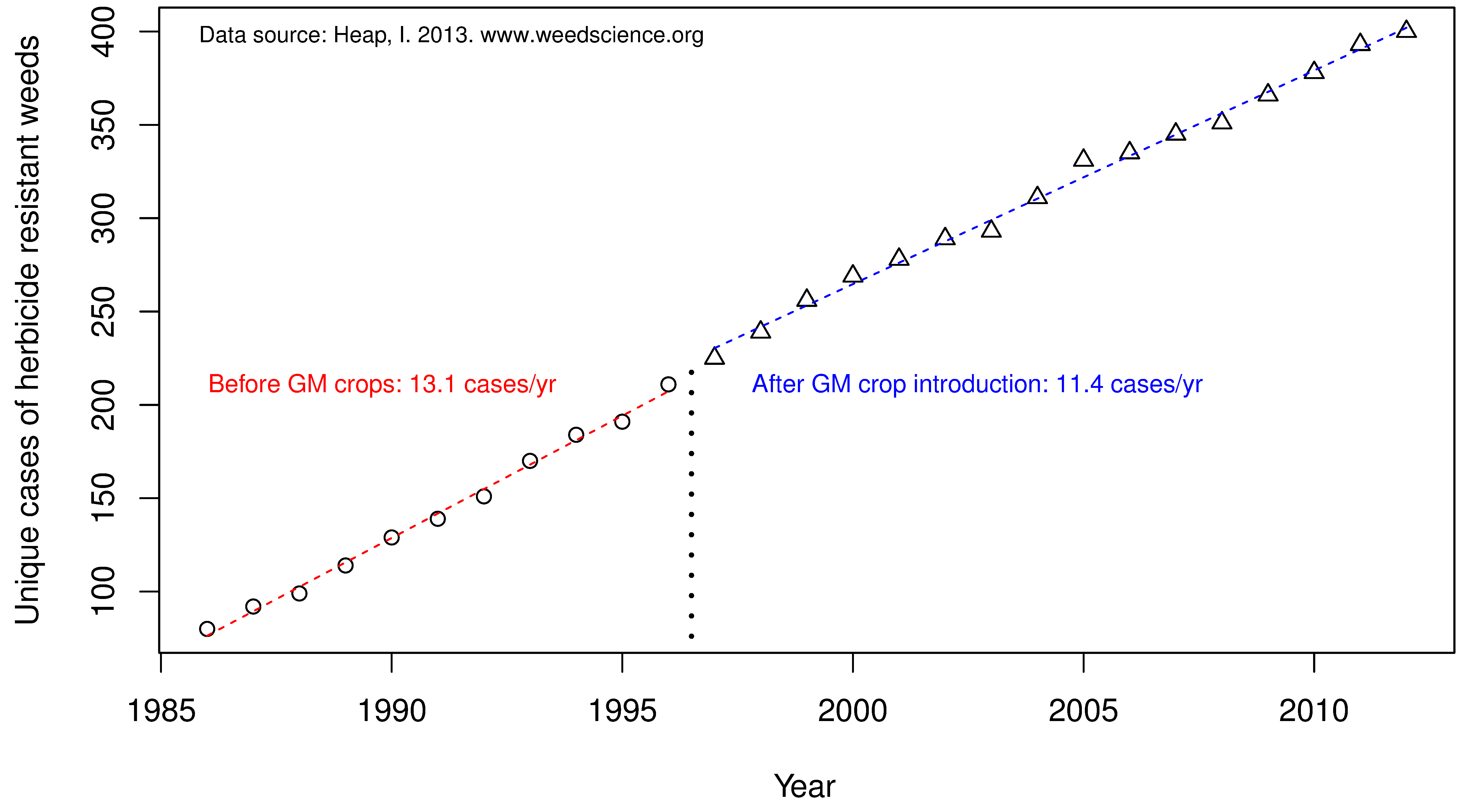

If GM crops have contributed significantly to the development of herbicide resistant weeds, we would expect the number of unique instances of these superweeds to increase following adoption of GM crops. The figure below illustrates all unique cases of herbicide resistant weeds between 1986 and 2012. I have fit a linear regression to the data from 1986 to 1996 (time period before widespread GM crop adoption) and another regression to the time period 1997 to 2012.

The slope of the linear regression is an estimate of the number of new herbicide resistant weeds documented each year. In the eleven year period before GM crops were widely grown, approximately 13 new cases of herbicide resistance were documented annually. After GM crop adoption began in earnest, the number of new herbicide resistant weeds DECREASED to 11.4 cases per year. The difference in slopes between these two time periods is probably not very meaningful from a practical standpoint. But based on the best data available, we can be quite certain that adoption of GM crops has NOT caused an increase in development of superweeds compared to other uses of herbicides.

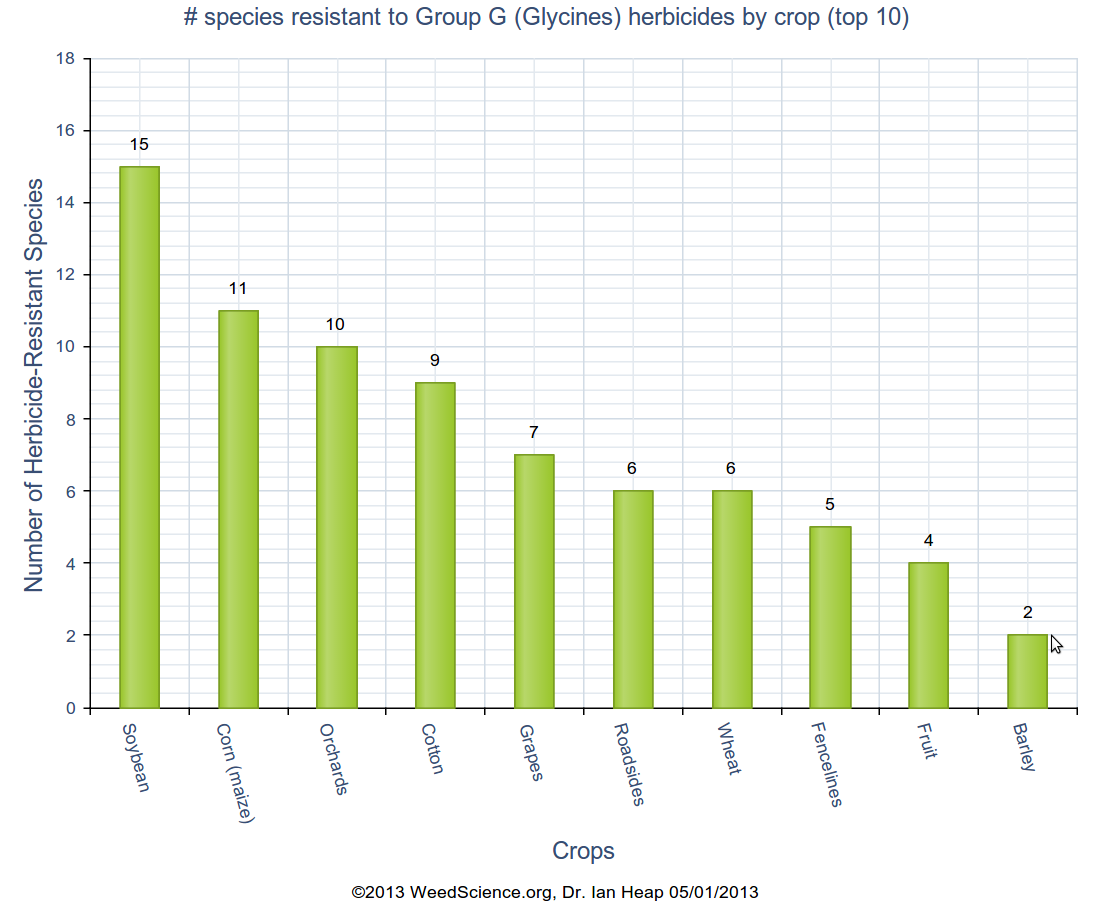

Perhaps this definition of superweed is too broad. Let’s define it instead as only “glyphosate-resistant” weeds. The first glyphosate-resistant weed was documented in 1996. This is approximately the same time GM crops were first being introduced into the market. But this first superweed evolved in Australia, where no GM crops were grown. So it is obvious that GM crops are not necessary for glyphosate-resistant superweeds to develop. Certainly, adoption of Roundup Ready crops (the dominant GM herbicide resistance trait) has increased the use of glyphosate in cropland, and therefore increased selection pressure for glyphosate-resistant weed populations. But even so, there are currently more instances of glyphosate-resistant weeds in non-GM crops/sites than in GM crops. The following chart (from www.weedscience.org) illustrates the number of cases of glyphosate-resistant weed species in various crops/sites.

The only 3 GM crops on the chart are soybean, corn, and cotton. All of the other bars represent non-GM systems. If we add up the number of herbicide resistant species in GM crops and compare it to non-GM crops/sites, we should expect GM crops to have a higher number if GM crops are the primary contributor to evolution of superweeds. However:

- 35 species of glyphosate-resistant weeds are present in GM crops (soybean, corn, cotton).

- 40 species of glyphosate-resistant weeds are present in non-GM crops/sites (orchards, grapes, roadsides, wheat, fencelines, fruit, barley).

So again, there appears to be no strong difference between GM crops and other sites where glyphosate is used. So this data again suggest that GM crops are not any more problematic than other uses of glyphosate for selection of superweeds.

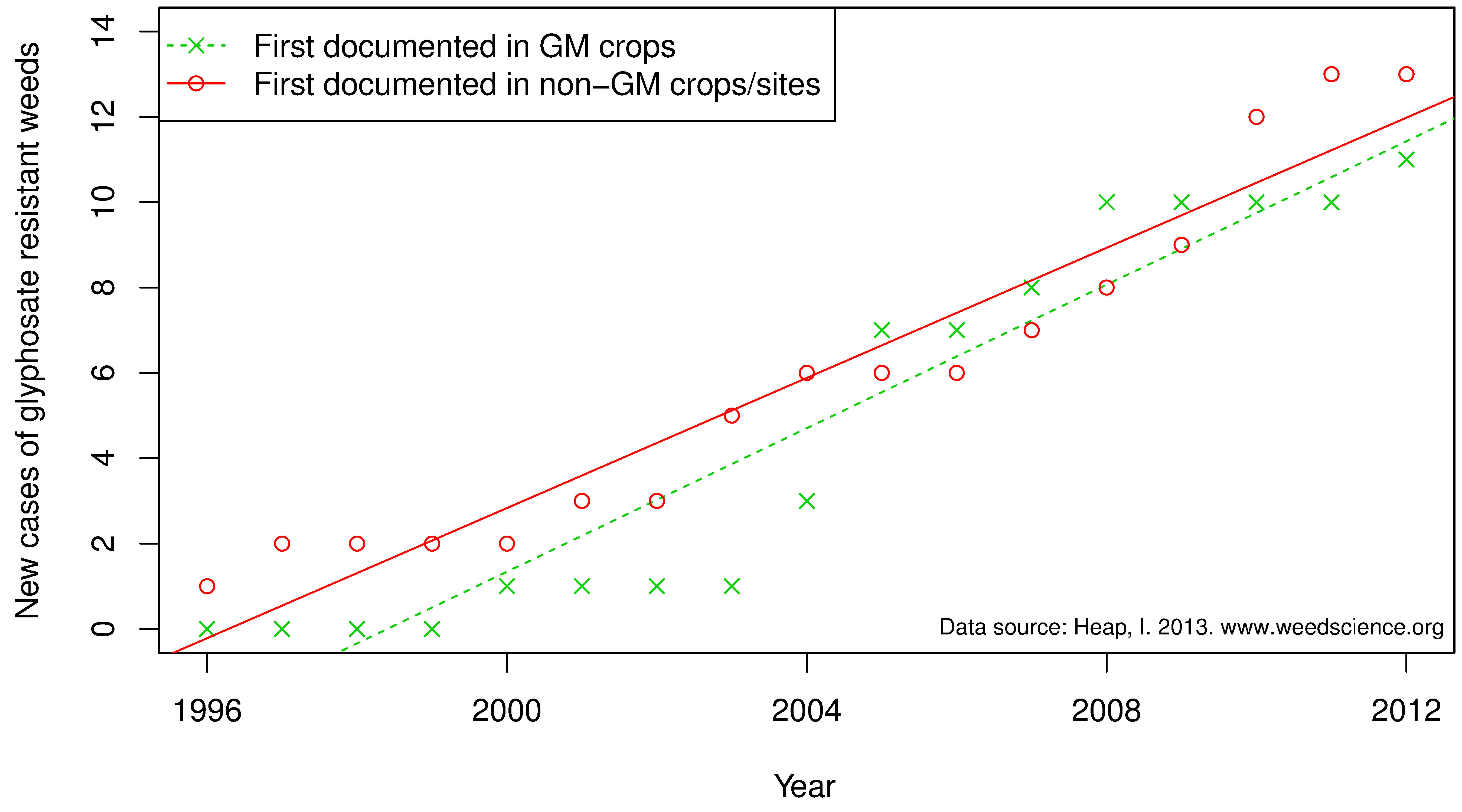

One deficiency in the above graph is that it doesn’t indicate where the weeds first evolved. Perhaps they evolved in GM crops, but then moved to infest other sites represented in the bar chart above. So instead, let’s take a look at WHERE the glyphosate-resistant weed species FIRST EVOLVED. Of the 24 glyphosate-resistant species documented worldwide, 11 of these superweeds first evolved in GM crops; compared to 13 superweeds that have evolved in non-GM crops/sites. Read those numbers again. And check out the figure below, looking at where and when glyphosate-resistant superweeds first evolved.

Almost any way you look at the data, it appears that GM crops are no greater contributor to the evolution of superweeds than other uses of herbicides. Which makes sense, because GM crops don’t select for herbicide resistant weeds; herbicides do. Herbicide resistant weed development is not a GMO problem, it is a herbicide problem.

It is important to note that the glyphosate-resistant weed species that have had the most economic impact are those that evolved first in GM crops (in particular, the Palmer amaranth noted in Ms. Gilbert’s article). But this is primarily because it is these weed species that were the most economically damaging to begin with (before they acquired their super-powers). But the Palmer amaranth narrative is what leads many people to conclude that glyphosate-resistant weeds are primarily a problem in GM crops. Certainly, Roundup Ready crops have increased the amount of glyphosate used in cropland, and this increased glyphosate use has contributed to the evolution of some new glyphosate-resistant weeds. No one can dispute that. But glyphosate-resistant weeds evolved due to glyphosate use, not directly due to GM crops. And to date, there have been more new cases of glyphosate-resistant superweeds documented in non-GM crops/sites than in GM crops. So it is difficult to make the case that GM crops are any more problematic than other uses of herbicides with respect to superweed development. Unless, of course, you rely on dogma and speculation.

Now, can we PLEASE stop using the term superweed?

Comments are closed.