This is the third (and probably final) post in a series on industry funding of my weed science program. The previous posts on this topic are here (Part 1: On transparency, intimidation, and being called a shill) and here (Part 2: Who funds my weed science program?). In this post, I’ll mostly describe some of my personal experiences. It is important to note that my experiences are not necessarily representative of others. I suspect that my experiences might be similar to other scientists with similar roles, but there will obviously be differences. I’m not so presumptuous as to think I speak for all university scientists, or even all weed scientists. The following represents only my experiences and opinions.

This is the third (and probably final) post in a series on industry funding of my weed science program. The previous posts on this topic are here (Part 1: On transparency, intimidation, and being called a shill) and here (Part 2: Who funds my weed science program?). In this post, I’ll mostly describe some of my personal experiences. It is important to note that my experiences are not necessarily representative of others. I suspect that my experiences might be similar to other scientists with similar roles, but there will obviously be differences. I’m not so presumptuous as to think I speak for all university scientists, or even all weed scientists. The following represents only my experiences and opinions.

bias – (1) Prejudice in favor of or against one thing, person, or group compared with another, usually in a way considered to be unfair. (1.1) A concentration on or interest in one particular area or subject. [Oxford Dictionary]

When writing this piece, I learned that the very idea of bias is surprisingly complex. There is an entire wikipedia page devoted to listing different types of cognitive biases (more than 90 of them, by my count). Researchers (whether funded by industry, NGOs, or public grants) are human, and so it is certainly reasonable to assume they all have biases in one form or another. In fact, it would be naive for anyone to claim to be truly unbiased in all aspects of life (even you, dear reader). But how does this potential bias influence me, my research, and my opinions?

My research is often beneficial to industry

In my last post, I noted that I regularly collaborate with my colleagues in industry. I don’t think it will surprise anyone that this research is often favorable to the industry. But, in spite of periodic accusations, it isn’t because these companies are bribing me or twisting my arm to get ‘good’ data. There certainly could be some selection bias at work here; funding organizations that share my particular set of ideas and goals will probably be more likely to provide funding for my research program. And I personally can’t rule out some unconscious bias as a result of these relationships.

I recently explained one industry-funded research project that turned out favorable for the funding organization. And I’ve published several other journal articles (some industry-funded, some not) that were favorable to at least one industry product, be it a herbicide or GMO trait. Some examples:

- I’ve published two economic comparisons of Roundup Ready versus conventional sugarbeet, one using controlled field studies, and the other in farmers fields. Both showed that this GMO trait and herbicide combination increased the farmers’ economic returns by well over $100/acre. That’s a pretty positive result for Monsanto, a company who contributes funding to my program. Less intuitively, it was also pretty positive for Syngenta, a major supplier of sugarbeet seed that contains Monsanto’s Roundup Ready trait. I have also received research funding from Syngenta.

- I’ve published two papers on new potential herbicides for use in proso millet, carfentrazone and saflufenacil. Only one of those studies was funded by industry, but I have received funding from both companies that make and sell these herbicides (FMC and BASF) for various other projects.

- I published a long-term evaluation of a non-GMO herbicide resistance trait, that was mostly positive for the trait/herbicide combination (Clearfield wheat, from BASF). That particular study was publicly funded, but again, I have received funding from BASF for other projects.

In one of my previous posts, a reader commented:

“It looks to me (after perusing your articles) that there isn’t a pesticide or herbicide that you don’t love.” –Debra-Lou Hoffman

I’ve been reflecting on that comment for a couple days now, and it would certainly appear that my biases have led me to blog mostly about the beneficial aspects of pesticides and GMOs. I don’t actually think pesticides and GMOs have no down-side, but based solely on my blog posts, it would be difficult for me to argue with Debra-Lou. Perhaps it is simply that negative (and often incorrect) information about these tools is more likely to elicit a response from me. But I have, at times, also gotten so annoyed with my own ‘side’ that I responded. I do strive for balance in my writing. I try to acknowledge the problems with modern agriculture when I’m writing about most topics. At the same time, I try to avoid false balance. If the data are squarely on one side of an issue, like the safety of GMO crops, I’m not going to give the alternative theories much time.

Publishing negative results

Even though my work is often favorable for pesticide and biotech companies, if you look through my research publications there are actually quite a few examples where my results were not positive for the industry. In many cases, the results were negative even to the company who funded the research. But we published those results anyway. The funding source never tried to persuade me not to publish. And in some cases, they even provided helpful comments on the manuscripts before they were submitted.

- Several years ago, a colleague and I published a couple papers on a relatively new herbicide synergist. The company (BASF) that funded the research was also the company that produced the synergist, and they were hoping to market the new product for increased control of perennial weeds. The results? It didn’t work; at least not in our studies. From a land manager’s perspective, their product would be a waste of money. Not exactly what BASF was hoping for, but they made no attempt to prevent or delay publication of the results. Our conclusions from those papers:

- “…diflufenzopyr + dicamba does not generally improve Russian knapweed control with either standard or reduced rates of typical fall, auxinic herbicide treatments.” (Enloe & Kniss, IPSM, 2009)

- “…diflufenzopyr did not enhance Russian knapweed control with either aminopyralid or clopyralid and was slightly antagonistic with picloram.” (Enloe & Kniss, Weed Technol., 2009)

- I’ve been involved with two studies that showed the long-term impacts of over-reliance on Roundup Ready crops on weed populations. Both of these studies were funded by Monsanto, and neither ended up being particularly beneficial for them. These two publications were among my earliest research, but Monsanto didn’t stop funding my program because the data weren’t favorable to their product. In both cases, Monsanto scientists were keenly interested in learning about our results, and showed no interest in trying to influence the data or interpretation.

- DuPont once funded me and a colleague to investigate one of their new herbicides for use in fallow to control weeds in the year before winter wheat was planted. Our results? We got great weed control. But… the herbi

cide reduced the subsequent wheat yield by up to 90%! This result was particularly noteworthy because the herbicide applications were made 2 to 6 months before wheat planting. Nobody (including us) expected the herbicide to have such a large effect on the crop after that much time.”Although the maturing wheat plants looked normal, few seed were produced in the aminocyclopyrachlor treatments, and therefore preharvest wheat injury ratings of only 5% corresponded to yield losses ranging from 23 to 90%, depending on location. The high potential for winter wheat crop injury will almost certainly preclude the use of aminocyclopyrachlor in the fallow period immediately preceding winter wheat.” (Kniss & Lyon, 2011)

cide reduced the subsequent wheat yield by up to 90%! This result was particularly noteworthy because the herbicide applications were made 2 to 6 months before wheat planting. Nobody (including us) expected the herbicide to have such a large effect on the crop after that much time.”Although the maturing wheat plants looked normal, few seed were produced in the aminocyclopyrachlor treatments, and therefore preharvest wheat injury ratings of only 5% corresponded to yield losses ranging from 23 to 90%, depending on location. The high potential for winter wheat crop injury will almost certainly preclude the use of aminocyclopyrachlor in the fallow period immediately preceding winter wheat.” (Kniss & Lyon, 2011) - My most recent publication, although it was not funded by industry, shows severe weaknesses in an ecological indicator which has been used widely by other researchers to show benefits of GMO crops. I personally think our research uncovered enough flaws in the Environmental Impact Quotient (EIQ) methodology to question many of the conclusions based on the EIQ, at least with respect to herbicides. This include many of the claims with respect to herbicide resistant GMO crops.

This is not a complete list of studies that were potentially negative for the companies that I collaborate with. There are a few more ‘negative’ studies currently in the publication pipeline as well. I recognize this is not sufficient evidence to claim that I’m immune to the influence of industry funding. But I think it does demonstrate that I do my best to do good science and communicate interesting results, regardless of whether they are favorable or unfavorable to “Big Ag.” I’m not unique in this respect; nearly all of the scientists I know are far more interested in conducting and disseminating good science than keeping any particular funding source happy.

Suppression of results and influencing outcomes

Among the general public, perhaps the most common concern about industry funding of public scientists is the perception that the funding source directly influences the outcome or interpretation of a study, or they will prevent publication of results that are unfavorable. I can honestly say I’ve never felt pressure from any funding source to change results or alter my interpretation of data or my conclusions. I’ve never had a funding source attempt to prevent publication of results, and my university wouldn’t allow me to enter into an agreement which prevented publication of negative data. Again, I can’t speak to other scientists’ experiences, but I have to imagine this type of outright coercion or fraud is extremely rare. As a courtesy, I will allow the funding source to review a manuscript shortly before the time of submission for publication. Some (but not many) research agreements have required that I give the company a few weeks notice before submitting any data for publication. I can’t speak to their motivation for this requirement, but I suppose it is probably to give their lawyers time to file any patent protections if they hadn’t done so already. But no company has every tried to influence the final manuscript in any meaningful way.

There have been a few cases where I’ve been working with a brand new product, and the funding source asks that we not publish the results until after the product was commercialized. Requests like this are sometimes made when the industry partner doesn’t want to ‘tip their hand’ to their competitors. But if this is the case, there is always a well-defined time frame agreed upon before the research begins, perhaps up to 2 years. From my perspective, a 2 year embargo from the initiation of the project is often reasonable, because I typically need 2 years of field data to publish in a peer-reviewed journal anyway. In practice, the embargo rarely delays publication of those results.

I don’t collaborate on projects that don’t either interest me academically or help my stakeholders (or both). When an industry source contributes funding to my program, it is because we share a common interest or goal. Therefore, there is typically a two-way flow of information as the study is designed and conducted. I may ask the funding sources for the optimal rates or adjuvant systems if it is a herbicide trial. Or I may seek advice on planting rates and timings. I often ask the funding source what type of data would be most helpful for them if it is a more ecologically oriented study. These considerations will make the research more useful to the funding source, but will also help me design and conduct a study that I can use to give my stakeholders relevant and useful information. It is certainly possible that the information shared at the planning phase of the collaboration may influence the results of the study. Perhaps, for example, the funding source will request data collection parameters that are more likely to show their product in a favorable light. To guard against this potential source of bias, I typically try to view my study from a farmer’s (or competitor’s) point of view. I try to ensure that any competing products (and control treatments) included in the study are also given the best chance of success. The data I present in my annual reports, grower presentations, and journal articles typically involves the data that is most relevant to the real-world, regardless of whether the funding source was interested in those parameters or not.

Funding dictates which research actually gets done

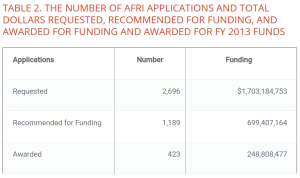

As a scientist, this is the type of bias that concerns me most; great research ideas regularly go unfunded, while at the same time research with relatively less potential impact is being done. This is not a direct influence of industry funding, but rather a lack of funding (public or private) for potentially interesting work. There is simply not enough money available to fund all of the interesting research ideas in agriculture. In 2013, the Agriculture & Food Research Initiative (AFRI) grant program within USDA only funded 16% of the grants that were submitted.  If that doesn’t sound depressing enough, it is even worse for certain disciplines. Only 14% of grants submitted for weed science or plant breeding were funded, and only 9% of grants related to biology of agricultural plants were funded. In 2013, over 750 grant applications to AFRI were deemed worthy of funding by the grant review panels, but were not awarded due to insufficient funds available. No funding, no research.

If that doesn’t sound depressing enough, it is even worse for certain disciplines. Only 14% of grants submitted for weed science or plant breeding were funded, and only 9% of grants related to biology of agricultural plants were funded. In 2013, over 750 grant applications to AFRI were deemed worthy of funding by the grant review panels, but were not awarded due to insufficient funds available. No funding, no research.

If industry is funding 50% of US agricultural research, we shouldn’t be surprised that about half of the research relates to pesticides, GMO traits, and other products sold by industry. There is simply not much motivation for most for-profit multinational corporations to fund locally-relevant research on cover crops or tillage practices. Even so, it is important to recognize that “Big Ag” funds some really cool science, too. One of the best papers on herbicide resistance I’ve read this year was funded jointly by USDA, Monsanto, and soybean growers. Some fascinating research that got me interested in shade avoidance was funded in part by Syngenta. And I’ve had various ecological projects (like weed seed longevity) funded by industry that will be leading to publications soon as well. If I were to shun industry funding in an attempt to become “pure” from an ideological standpoint, it wouldn’t change the fact that there isn’t enough public funding to support all of the work I want to do. So I’d just end up doing less research. And I, personally, don’t see how that would help the stakeholders I’m trying to serve.

I want you to be skeptical of my work

The original working title of this post was “Does my funding influence me?” But I didn’t get too far into writing before I changed it to the current title. Because let’s be honest: everyone has biases. That is simply part of being human. The important thing, in my opinion, is not to eliminate all sources of potential bias; that would be impossible. But we can make an effort to acknowledge and regularly examine potential biases, especially our own. It would be naive of me to claim that my funding has no influence over me whatsoever. The scientific literature on funding bias is pretty clear. Medical studies are more likely to find favorable results for a new treatment if the research is funded by industry. Although I’m not aware of any similar analyses of agriculture research, I’d be surprised if there weren’t a similar trend.

So I’ll end this series of posts with a request: please scrutinize my work. I fully expect that people will be more skeptical of my research if it is funded by Monsanto than if it were funded by the USDA. In the minds of some people, the very fact that I receive any funding from Monsanto and BASF and DuPont will make my opinions and my research questionable. And on the other side, there are many folks who become immediately skeptical of any work funded by the Organic Center or Environmental Working Group. But here’s the thing: opinions and research should be scrutinized, regardless of the funding source. Viewing claims and opinions and data with a skeptical eye is what makes science better. If you don’t believe what I say, ask for evidence. Perhaps even more importantly, if you do believe what I say, ask for evidence. Check to see if what I say conflicts with the majority of experts in my field. It doesn’t matter whether I’m funded by Greenpeace or Monsanto, if I make a claim that isn’t supported by evidence, then you should call me out. And this should be done for all experts, not just those you disagree with.

Comments are closed.