Dan Charles at NPR has recently done two interesting pieces about sugar production. In the first, he uses sugar as a proxy to look at the environmental costs and trade-offs of growing food in different places. It makes for an interesting comparison because there are two completely different crops (sugarcane and sugarbeet) that can be grown to produce the exact same product, refined sugar. The two crops have very different climatic needs, pest management requirements, and growing seasons. It is an interesting read.

The second piece, which I found even more interesting, reports on the impact of some major sugar buyers have had by moving away from sugar produced by GMO sugarbeet:

Deborah Arcoleo, director of product transparency at the Hershey Co., told me that in 2015, “we started reformulating Hershey’s Kisses, Hershey’s milk chocolate, and Hershey’s milk chocolate with almonds, to move from beet sugar to cane sugar, and that’s complete. Now we’re looking to do that across the rest of our portfolio, to the extent that we can.”

Hershey’s is one of the top sugar users in the country, and other companies have made similar moves.

The result has been a remarkable change in the American sugar market. Slowly, but consistently, a gap has opened up between the price of sugar from cane and sugar from beets.

“The current price for beet sugar is about 3 to 5 cents below the price for cane sugar on the spot market,” says Michael McConnell, an economist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service.

It means that buyers are paying 10 to 15 percent more for cane sugar.

In order to respond to these recent changes, Dan Charles says that US sugarbeet farmers “are thinking about going back to growing non-GMO beets.” This may seem like a trivial change to people not actively engaged in the sugarbeet industry. But for a sugarbeet farmer to even consider this is nothing less than remarkable.

I’ve previously written about some of the drastic changes that farmers experienced in the transition from conventional to GMO sugarbeet production. Duane Grant, a sugarbeet grower in Idaho, was interviewed just a few years ago about the prospect of moving back to non-GMO sugarbeet:

Part of Grant’s intense interest in [GMO] beets definitely stemmed from his own farm’s experiences with the “traditional regimen” of herbicide products and application timing and methods. “It was a nightmare,” he recalls of those pre-Roundup days. “We had failures all the time — fields that would become unharvestable because of our failure to control weeds. We had an army of people applying herbicides around the clock or just at night. We did micro-rates, we did maxi-rates, you name it.”

“We had one sprayer for every 500 acres, so eight sprayers running around,” Grant relates. “They would work whenever they could. It might be all night long; it might be 24 hours straight because they had a window.

“It was a horrible life. Just last spring (of 2011), as the Roundup litigation was progressing through the courts and it was unclear whether we’d be able to plant Roundup Ready seed, my sugarbeet manager flat-out told me, ‘If we have to be conventional again, I’m quitting. I can’t do it.’

“I’m so glad we got to plant Roundup Ready beets!”

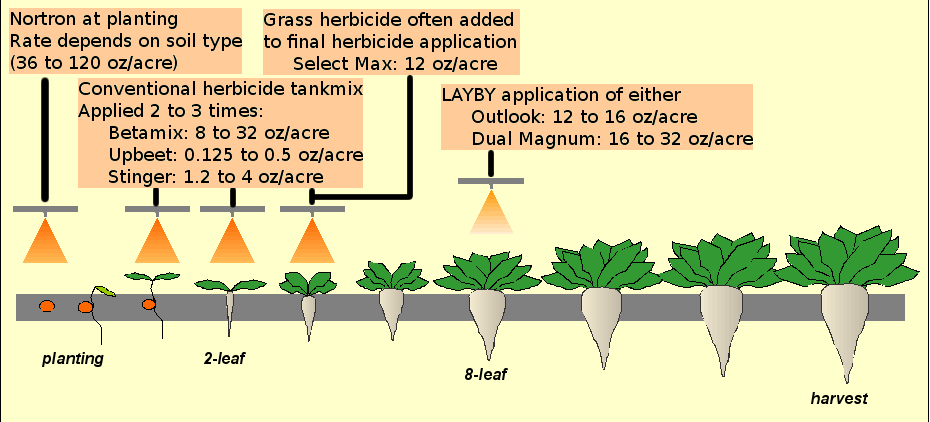

Sugarbeet growers are not exaggerating when they talk about the drastic shift they observed in the switch to GMO seed. The herbicide regimen used to include 4 to 6 different herbicides applied between 3 to 6 times per year, at 5 to 10 day intervals.

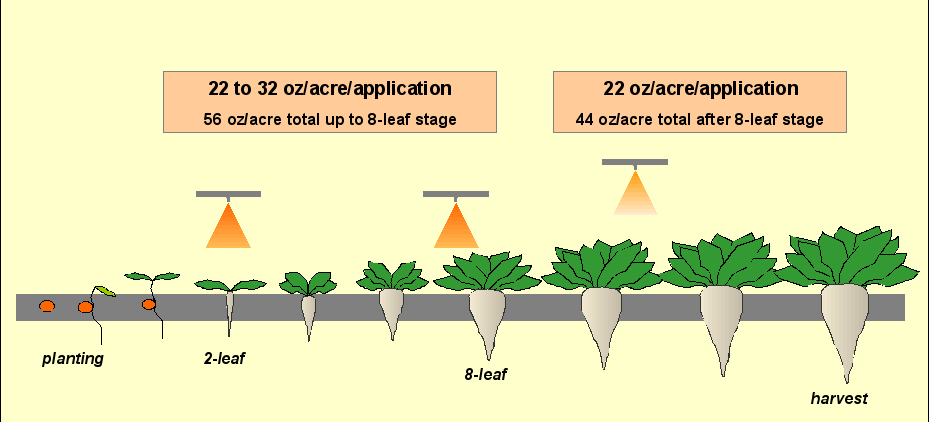

Even after this much herbicide spraying, Around 40 to 60% of sugarbeet fields had to be hand-weeded because the herbicides rarely provided complete weed control. Compare that to the Roundup Ready (GMO) system, where 2 or 3 applications of glyphosate have replaced the many herbicide sprays that were used previously, while providing better weed control.

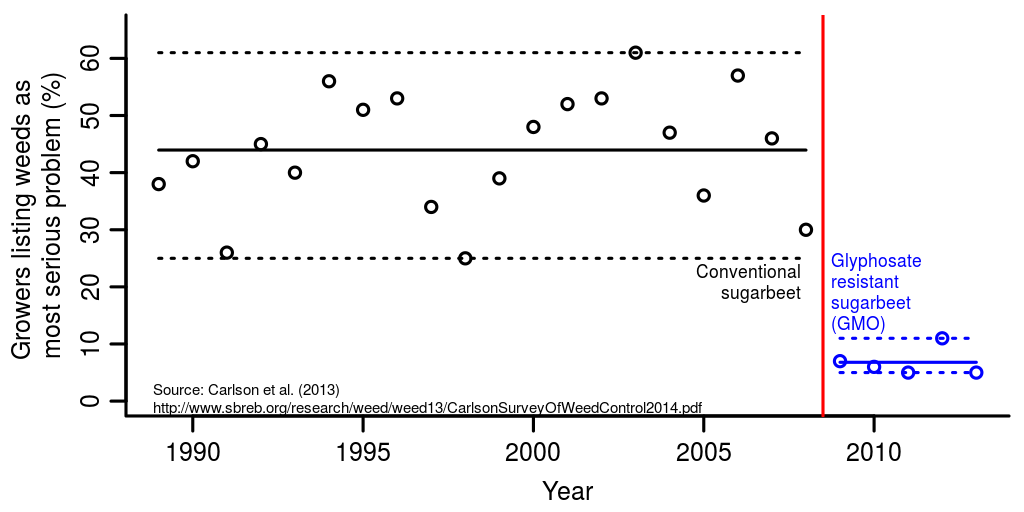

The Roundup Ready system has resulted in unprecedented levels of weed control. The North Dakota/Minnesota sugarbeet grower survey has tracked weed control practices in sugarbeet production for many years. Before the adoption of GMO sugarbeet, an average of 45% of farmers listed weeds as their most serious production problem from year to year. After the adoption of Roundup Ready beets, that dropped to fewer than 15%.

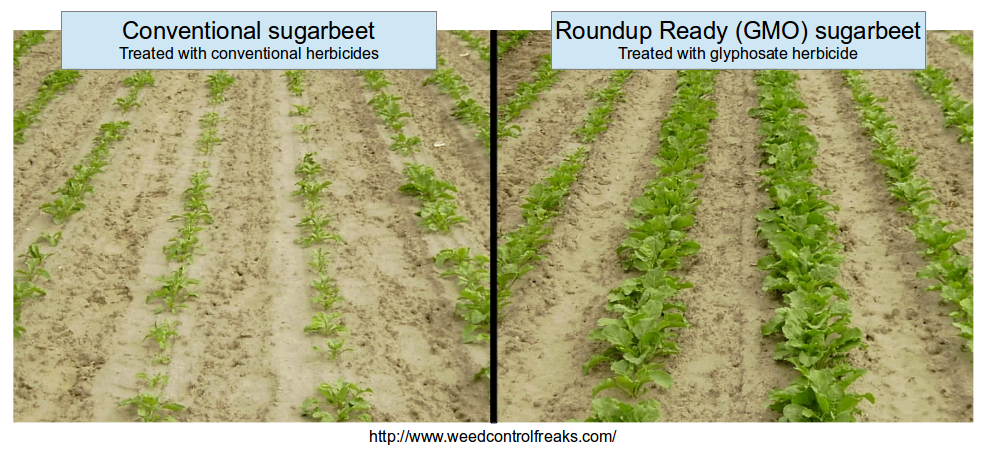

But it isn’t just the simplicity or the significantly improved weed control of the Roundup Ready sugarbeet system that convinced farmers to switch. Conventional sugarbeet herbicides can cause severe injury under adverse environmental conditions. Some growers refer to conventional sugarbeet herbicides as ‘chemotherapy’ for the beets. They injure and weaken the beets, but they hurt the weeds a little more. This is why the conventional herbicides were often applied multiple times at short time intervals. A higher, one-time dose of the herbicides would provide better weed control, but it would also cause more severe injury to the beet crop. As with chemotherapy, the weeds would eventually die after several applications, but the beets would be substantially weakened (like the photo on the left in the figure below). Conversely, Roundup applied to Roundup Ready sugarbeet (photo on the right) virtually eliminated the potential for crop injury due to herbicides.

The improved weed control provided by Roundup Ready varieties led to rapid environmental gains. By 2009, only two years after widespread adoption of GMO sugarbeet, over 50,000 acres of sugarbeet fields were converted to some form of reduced or conservation tillage practices in Nebraska, Colorado, and Wyoming. That number is probably much higher now. Conservation tillage practices improve soil health, reduce soil erosion, and preserve soil moisture. Conservation tillage simply wasn’t possible in sugarbeet before the introduction of Roundup Ready varieties, because intensive tillage was needed to obtain adequate weed control in the crop.

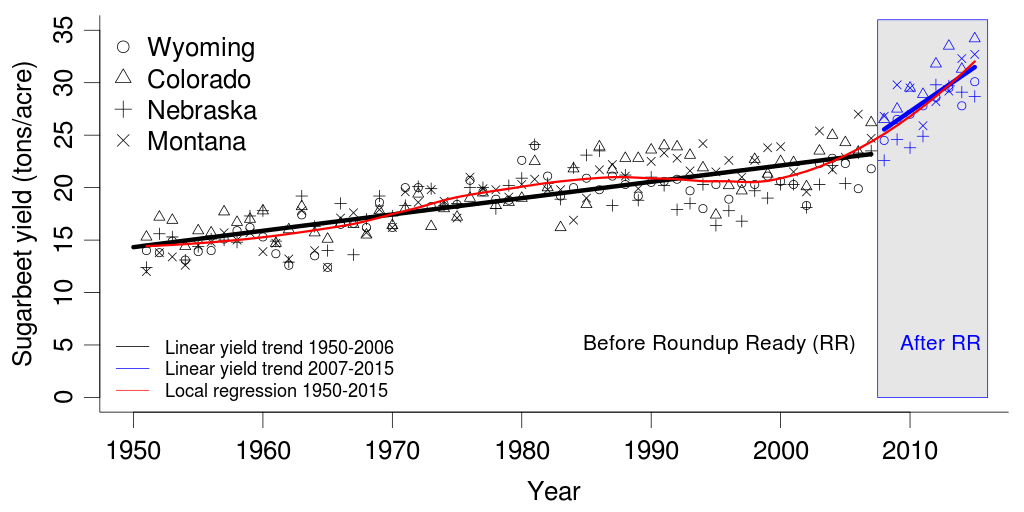

The combination of improved tillage, reduced crop injury, and improved weed control has contributed significantly to increased sugarbeet yields in the High Plains growing region. Not all of the yield gains can be attributed directly to GMO, but I would suspect it is a substantial proportion.

So to summarize, GMO sugarbeet has reduced herbicide use, increased soil health, decreased risk of crop injury, increased yield, and has even allowed farmers to spend more time with their families. Knowing all of that, I was struck by the last line of Dan Charles’ piece, where a sugarbeet grower, Andrew Beyer, is quoted:

“To me, it’s insane to think that a non-GMO beet is going to be better for the environment, the world, or the consumer.”

But Beyer says he’ll do it if he needs to. He’ll do what his customers want.

Andrew Beyer isn’t being facetious when he says he thinks GMO sugarbeets are better for the environment, the world, and the consumer. He truly believes it, as do most sugarbeet farmers in the US. And the data suggests they’re right.

But these same farmers are willing to grow what the customer wants. If Hershey’s and others want a non-GMO sticker on their candy badly enough, sugarbeet growers will go back to producing non-GMO sugarbeets. Even if it means abandoning all the benefits this technology has provided.

Comments are closed.