A little over a week ago, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) announced that glyphosate would be added to their list of agents that are “probably carcinogenic to humans.” Glyphosate wasn’t the only pesticide added to the list, but as Nathanael Johnson noted at Grist, glyphosate tends to be something of a lightning rod due to its association with genetically engineered (Roundup Ready) crops. Let me start by pointing out I’m pretty late to the party writing about this. The IARC is a well-respected agency within the World Health Organization, so this announcement has been widely reported. And it should surprise nobody that Monsanto is vehemently denying any health concerns, while the usual suspects who oppose GMOs and pesticides are using it to advance their agendas. I think the aforementioned piece by Nathanael Johnson at Grist and a piece by Dan Charles at NPR do a good job of putting this new classification into context. Grist also posted a really cool video that explains what the IARC group 2A classification (“probably carcinogenic to humans”) actually means.

Rather than simply re-state what others have said on the topic, I wanted to actually take a thorough look at the evidence supporting this classification. I work with pesticides (especially glyphosate) on a regular basis, so I take this classification very seriously. If glyphosate is indeed likely to cause cancer, I am in the group of people who is most likely to be affected. As most of the reasonable write-ups have previously noted, IARC group 2A agents are problematic mostly for occupational exposure; that is, people who work with (or around) the chemical on a regular basis over a long period of time. The general public is highly unlikely to see any ill effects from any agent with this classification based on available evidence. I’m disappointed that IARC decided to announce the classification about a year before they plan to release the full monograph that details their reason for the decision. Having their list of references sure would have been useful to determine which data they’re using to come to that conclusion. So I did a literature search for studies that included glyphosate and cancer. A recent review article by Pamela Mink et al. (2012) provided a nice starting point. It should be noted that the review article was funded by Monsanto; however, I didn’t actually rely on the conclusions of the Mink paper, so that potential conflict is mostly irrelevant. I simply used the Mink article as a starting point to find research articles that investigated the link between glyphosate and cancer.

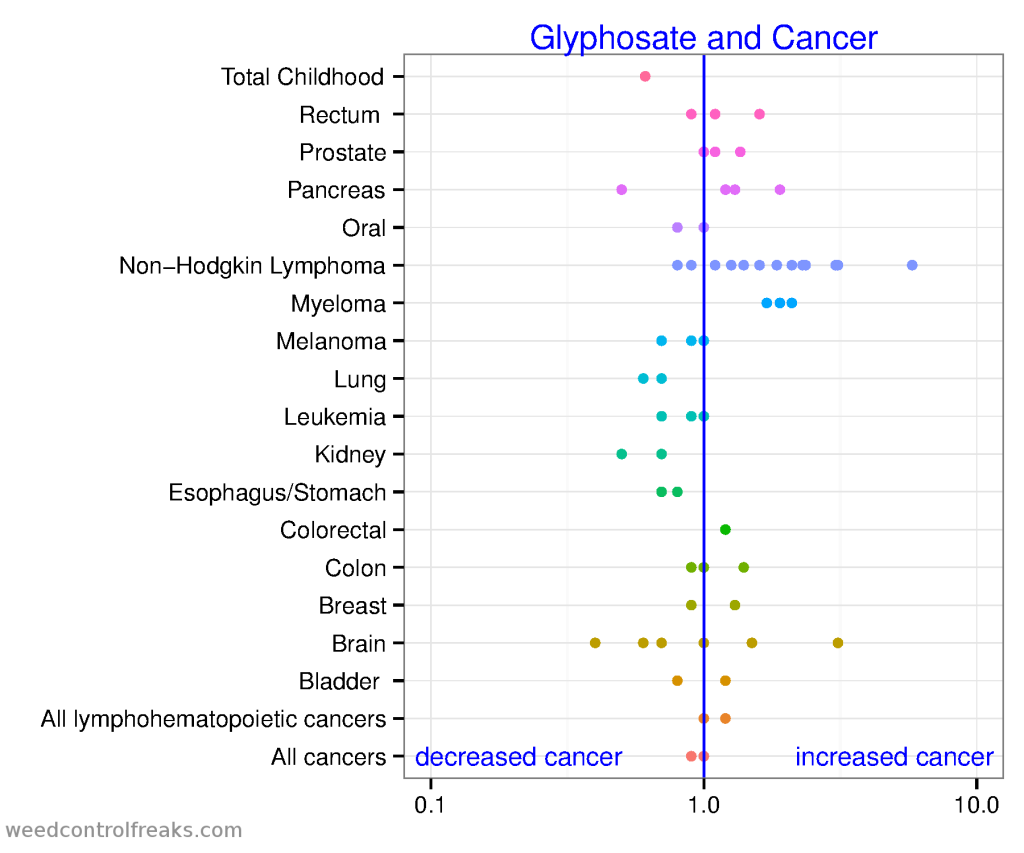

Recently, Vox presented a very nice figure that summarized why you shouldn’t put too much faith in any single study about things that cause or cure cancer. I used that as a model to create this figure, which summarizes all of the information I could find relating glyphosate exposure to cancer.

In the figure, each point represents the relative risk of developing cancer between people who had been exposed to glyphosate and those who hadn’t. To interpret the figure, any points on the left side of the blue line (less than 1) means that, on average, people who were exposed to glyphosate were less likely to get that type of cancer. Points to the right of the blue line mean that people exposed to glyphosate were more likely to get that type of cancer. There are two important things to note about this figure. First, this is an obvious over-simplification of the data. Presenting the data this way excludes the uncertainty of the relative risk estimates. When a study presents these estimates, they usually also present 95% confidence intervals. Those intervals are critical to determining whether we should put much faith in the estimate. Generally speaking, if the confidence interval spans across 1, then we would conclude that the evidence is too weak to suggest any causal link. Even so, if we have similar numbers of points to the left and right of 1, or the points are all clustered very close to 1, we can safely conclude there is little evidence of a link.

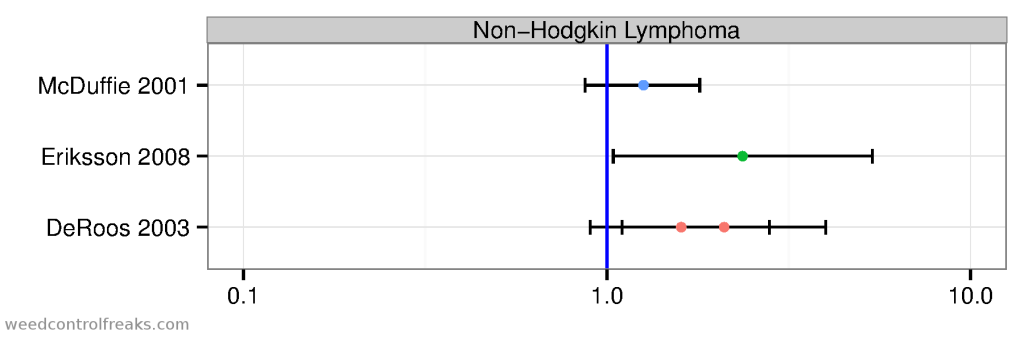

The second point about the figure above is that there appear to be many points on the right side for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. This is important, because that is the type of cancer specifically called out in the Lancet Oncology article that the IARC used to officially announce their new classification. The table on the first page of the Lancet paper states that “Evidence in humans” is “Limited”, with the cancer site listed as “non-Hodgkin lymphoma.” The Lancet Oncology paper lists only 16 references, and as far as I could tell, only 3 of those references actually contained information on glyphosate and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (henceforth referred to as NHL). And those 3 references do seem to suggest a link between glyphosate exposure and NHL.

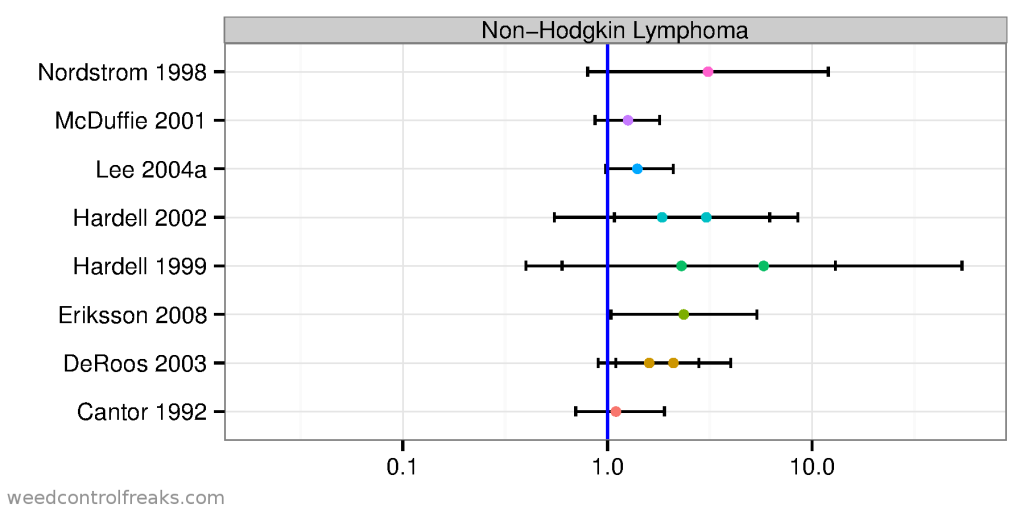

All three of the studies in this figure are “case control” studies. This type of study takes a large number of ‘cases’ of the disease of interest, finds a similar group of people without the disease, and then tries to find differences in risk factors between the groups. Any factors that are more prevalent in the ‘case’ group (the group with the disease) are viewed as possible risk factors for the disease. Case control studies can be very useful, as Vox points out here. In the three case control studies referenced in the IARC Lancet paper, all of the point estimates are to the right of 1. But the confidence interval from McDuffie et al. (2001) paper includes 1, indicating that the evidence for a link in that study wasn’t very strong. Similarly, DeRoos et al. (2003) used 2 different models, and the confidence interval for one of those models contained 1. As I looked through a variety of case control studies, multiple models were common. The authors would sometimes evaluate 2 or even 3 different models comparing glyphosate-exposed and non-exposed people. More on this later. I was able to find several more studies (in addition to the 3 that IARC referenced) that investigated links between glyphosate and NHL. All of those studies are summarized in the figure below:

Although many of the confidence intervals contain 1, all of the point estimates are greater than 1. So although there is a lot of variability in the data, the association of glyphosate exposure and NHL does seem to be reasonably consistent across studies. Perhaps this is what the IARC panel saw when they arrived at their conclusion. Similar to DeRoos (2003), both Hardell studies employed more than 1 model. In the studies I read, the difference between models was usually an attempt to adjust for confounding variables. The most common confounding variable in the NHL studies was exposure to other pesticides. A very large percentage of people who are exposed to glyphosate for long periods are also exposed to many other types of pesticides. This is a very important limitation of case control studies. Most people who use glyphosate a lot (like farmers, commercial pesticide applicators, and weed scientists) tend to be exposed to many compounds that are much more rare among the general public. We certainly tend to use a variety of pesticides, but probably also inhale more dust and fertilizers. We are out in the sun a lot. We probably also get exposed to more hydraulic fluid and wake up earlier than the general population. These things are extremely difficult to control for in a case control study.

Additionally, in the case control studies I read, a very small minority of NHL cases were actually exposed to glyphosate. For example, only 97 people (3.8% of the study population) had been exposed to glyphosate in the DeRoos (2003) study. Similarly, only 47 people (2.4% of the study population) had been exposed to glyphosate in the Eriksson (2008) study. These are very small numbers. To look at it another way, only about 3% of the NHL cases in most of the case control studies had actually been exposed to glyphosate. So even if glyphosate does increase the risk, it certainly is not a major contributor to NHL cases in the general population.

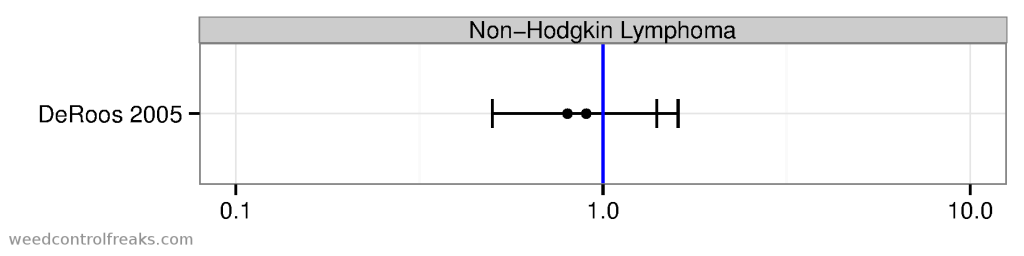

But case control studies aren’t the only types of studies that have been used to investigate the link between glyphosate and cancer. DeRoos et al. conducted a follow up to their 2003 study using a different, and arguably better methodology. Cohort studies follow a group of people during some portion (or all, depending on the study) of their lives, and track many risk factors and health outcomes. DeRoos et al. (2005) looked at a group of 54,315 agricultural workers. Once again they used two different models in their analysis, but the results of this study were contrary to what was observed in the case control studies.

The point estimates were actually less than 1.0, with confidence intervals that contain 1. These results suggest there is no discernible link between glyphosate and non-Hodgkin lymphoma among a population where glyphosate use is the most common. Over 41,000 of the 54,315 study participants had been exposed to glyphosate in this study. And 99.82% of them did not get non-Hodgkin lymphoma during the course of the study.

So what does this all mean? I may change my mind when the IARC’s full monograph is published later, but based on the data I could find, I don’t see any evidence for alarm. And I say that as someone who is exposed to more glyphosate than a vast majority of the population. There is nothing here that I think can tarnish glyphosate’s reputation as a very safe pesticide. But that doesn’t mean that we should throw caution to the wind and douse ourselves in it. And for god’s sake, please stop saying things like “glyphosate is safe enough to drink.” Drinking Roundup doesn’t prove anything, anyway. I could smoke a cigarette and drink a beer in front of a crowd, but that doesn’t make alcohol and cigarettes any less responsible for causing cancers. Glyphosate is still a pesticide, after all. Proper protective equipment and procedures should be followed when any pesticide is used. But when used according to label directions, I think there is no reason to be scared whether you’re a homeowner trying to get rid of weeds in your sidewalk, or a commercial applicator spraying 1,000 acres of Roundup Ready corn.

Suggested links:

So Roundup “probably” causes cancer. This means what, exactly? by Nathanael Johnson, Grist

A top weed killer could cause cancer. Should we be scared? by Dan Charles, NPR

He’s not a Monsanto lobbyist, and weed killer isn’t safe to drink. by Matthew Herper, Forbes

Watch stick figures explain what “probably causes cancer” even means. by Suzanne Jacobs, Grist

Weed killer, long cleared, is doubted. Andrew Pollack, New York Times

Monsanto’s statement on the IARC classification of glyphosate. Monsanto

Glyphosate as a carcinogen, explained. Farmers Daughter USA

Roundup and Risk Assessment. Michael Specter, The New Yorker

Comments are closed.